Bony fishes (Osteichthyes) are divided into two main groupings: the ray-fins (actinopterygians) and the lobe-fins (sarcopterygians). Nearly all the bony fish around today are ray-fins — lungfish and coelacanth being the only surviving lobe-fins. During the Paleozoic era there were a great many more lobe-fins, including groups that are now extinct, like the rhizodontids.

Letognathus was up to 5 meters (16 ft.) long and could weigh about 3-tons.

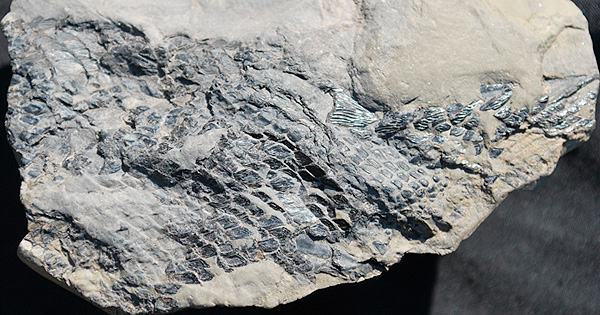

Maxilla (upper jawbone) of Letognathus, top predator of Blue Beach

The best-known vertebrate creature from Blue Beach is Letognathus, the rhizodont, with over 2500 specimens now at the BBFM. This is the only site in Canada known to contain rhizodonts. Letognathus means “jaws of death, annihilation or ruin”, and it was a fish that could grow to about 5 meters long (16 ft.). It was a remarkable predator that had numerous sharp teeth of several different shapes and sizes, all within the same mouth.

Like many other lobe-fins, the strong skeleton and musculature of the front fins actually enabled this fish to lift itself out of the water and crawl. They also possessed rudimentary lungs and could breath air.

Letognathus was a top predator of the early Carboniferous. It was an ‘ambush predator’, preferring to wait patiently for the unwary to venture too close. Like alligators, they could spring into action, snapping up surprised fishes or tetrapods. When their prey was too large to swallow whole, rhizodonts probably thrashed their prey like the alligators of today, perhaps dragging them back to the deep water.

Scientists still know very little about these enigmatic fish because nobody has ever found a complete adult skeleton. Most of what we know about them comes from fragmentary or incomplete material. The abundance of remains from Blue Beach is destined to make Letognathus the best-known rhizodont ever. By examining each fossil bone, a little more knowledge is gained toward an understanding the whole skeleton. Common finds include teeth and scales. Less common are platy skull bones or elements of the fin or shoulder. Scarce specimens like the impressive jawbones with teeth, which gave these creatures their terrifying name, are still discovered at least once every year.

The stout humerus shows why rhizodonts were able to support themselves on their fins.

Lungfishes – A second lobe-fin known from the fossils at Blue Beach is a fairly large lungfish tentatively identified as Ctenodus. Very few examples are known, suggesting the population was quite small. Lungfishes are usually fairly common finds at other early tetrapod localities, but not so at Blue Beach. This shoreline seems to have had too many rhizodonts!

Like their name implies, lungfishes had lungs and could breath air. They probably ambushed prey like the larger rhizodonts rather than swimming around looking for meals. Lungfish bones are even more easily confused with tetrapod bones than are rhizodonts, so identifications at are sometimes necessarily tentative ones.

Ray-finned fishes – Palaeoniscoids were early ray-finned fishes, ancestral to most of today’s bony fish (such as herring, salmon, and anything in your fridge or fishtank!).

Palaeoniscoids were coated in a bony coat of shiny scales. Palaeoniscoid scales are extremely numerous, but patches of the whole skin like this are scarce.

Their shiny scales and other bony parts are found in great numbers in some Blue Beach rocks. Species of Elonichthys, Rhadinichthys, and Canobius are fairly common. A large form plus a new deep-bodied form are also present. As far as predators go, the palaeoniscoids weren’t all that large, yet they were quite successful. This was partly because they were fairly clever, quick and agile. They also likely traveled in large schools for safety-sake.

Acanthodians – The common name “spiny sharks” gives a false impression that these fish are related to the elasmobranches (true sharks). Instead, the acanthodians are a very primitive group of jawed fish whose relationships with other groups remains in question. They have very few bony parts – most notably they have spines that project in front of the fins, and these bony spines are the most common parts found. These fish had a lower jaw bone (mandible) but were toothless, so they are believed to have been filter-feeders – vacuuming up small organisms as they swam about. Also, having so few bony parts meant they were lightweight fishes that probably did not swim along the bottom. The spines were strictly defensive, there to discourage larger predators from swallowing the otherwise defenceless acanthodians.

Ornate fin-spines of Gyracanthides are usually found as fragments. This complete spine is a rare find.

Elasmobranches – Most sharks over time have lived in the salty waters of the oceans, but some Carboniferous types were adapted to freshwater. These fish also developed bony spines. Like acanthodians, they built their skeletons mainly out of cartilage. Ctenacanthus from Blue Beach is known almost strictly from its spines. A single mandible with rounded teeth suggest they might have fed on shelly-creatures, as this kind of specialized dentition is usually used to crush and break through shells.